Let’s talk about the Netflix adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem,” particularly its depiction of the Cultural Revolution and why we need more film and television dramas that portray the Cultural Revolution.

As everyone knows, this Netflix version of “The Three-Body Problem” was released yesterday and has become very popular. This inevitably makes us want to recall the journey of turning “The Three-Body Problem” into a film or TV series.

“The Three-Body Problem” is very popular in China. I saw a statistic stating that it has sold 7 million copies, but the number is likely higher now.

I’ve checked the records for the best-selling books in China according to Wikipedia; the data might not be complete, but it gives us a point of reference.

Of course, the best-selling book in Chinese history would probably be “Selected Works of Mao Zedong,” printed in 1.8 billion copies. Generally, it’s said that “Dream of the Red Chamber” has a circulation of 100 million.

“The Wolf Totem” has sold around 20 million copies. There’s also an unexpected book I hadn’t heard of before called “Research on Socialist Economic Issues in China,” by Xue Muqiao. In 1979, right after the Cultural Revolution ended, there was a high demand for a book studying China’s economy. That book sold over 10 million copies in three years, but probably no one looks at it now. At that specific time, everyone was concerned about how to manage the socialist economy. After the reform and opening up, I guess people weren’t that concerned about this issue anymore.

So, Liu Cixin’s “The Three-Body Problem” selling over 7 million copies is already quite remarkable.

This situation is quite extraordinary, and now it might be hard for many people to understand. The book was published in 2008, and by 2009, an up-and-coming director named Zhang Fanfan bought the rights to “The Three-Body Problem” from Liu Cixin for just 100,000 yuan, acquiring all the film and TV rights for the following five years.

By 2014, Zhang Fanfan had partnered with Yoozoo Pictures (a subsidiary established by the game company Yoozoo Network to focus on films) to start the production of “The Three-Body Problem.” Celebrities like Zhang Jingchu, Feng Shaofeng, Wu Gang, Tiffany Tang, Zhang Han, and Du Chun participated in the project.

In 2015, a rough cut of the movie was already available and there were rumors that it would be released soon. In November 2015, Li Yuanchao, then a member of the Central Political Bureau and Vice President of the country, inspected Yoozoo Network in Shanghai and watched this rough cut of the movie.

According to the people at Yoozoo Films, the leader did not give a very favorable review after watching it. Even the Yoozoo staff felt it wasn’t very satisfying. Consequently, the movie has never been released. There have been various rumors about when it might be released or what kind of modifications would be required, but the result has been that it has never been shown to the public.

This connection with the recently released Netflix adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem” and its segments on the Cultural Revolution has garnered widespread attention and discussion. Maybe Li Yuanchao thought the film’s quality was too poor back then, or perhaps he found the depiction of the Cultural Revolution too explicit – it’s hard for us to know.

By December 2020, another significant news story related to “The Three-Body Problem” emerged. Lin Qi, the chairman of Yoozoo Pictures, was poisoned by Xu Yao, the CEO of a subsidiary company, Three-Body Universe, and eventually passed away despite attempts at treatment.

This incident occurred during the pandemic, and we witnessed the whole situation unfold online. Initially, there were reports that he had been poisoned, and eventually, Xu Yao was identified as the poisoner, leading to Lin Qi’s death. It was the hottest news at the time. Xu Yao’s reason for poisoning might also be linked to “The Three-Body Problem,” likely stemming from the film’s failure to be released and the ensuing internal blame within the company, which sparked Xu Yao’s dissatisfaction.

On January 15, 2023, a domestic version of “The Three-Body Problem” was launched. It first aired on CCTV and then was made available online, commonly referred to as the Tencent version of “The Three-Body Problem.” Yesterday, March 21st, Netflix’s version of “The Three-Body Problem” also went live.

This has led to a lot of discussions. There are debates over whether the depiction of the Cultural Revolution is exaggerated, whether it sufficiently represents the original work, etc. This includes questions about why the text in the Cultural Revolution scene is in print rather than handwritten, and explanations regarding the slogan “social imperialism” and what it signifies.

Then today, another major piece of news related to “The Three-Body Problem” broke – the Shanghai No. 1 Intermediate Court sentenced Xu Yao to death and deprived him of political rights for life.

The producer of the domestic version of “The Three-Body Problem” is Lin Qi, who was the chairman of Yoozoo Pictures and was tragically murdered. The TV series rights for the Netflix adaptation were also acquired from Yoozoo Pictures.

Now let’s talk about Netflix’s adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem” and its depiction of the Cultural Revolution. In fact, I’ve only watched the part about the Cultural Revolution in the Netflix adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem.” It’s approximately the first five minutes of the first episode. If you’ve read the novel “The Three-Body Problem,” you should know that this portrayal is actually quite similar to the book.

Even some people have criticized that it’s not as brutal as written in the novel, saying the novel is more sensational. I am quite satisfied with this depiction, although many people have various criticisms.

First of all, it’s important to note that Netflix’s adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem” is actually targeted at an international audience. As is well known, Netflix isn’t available in Mainland China. While it is accessible in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan, those regions have a relatively small population, just tens of millions. Some details are from the perspective of foreigners who mainly focus on the atmosphere and the exoticism. Certain fonts and terms are not comprehensible to them. But as for the sense of atmosphere, I feel it has been well-restored.

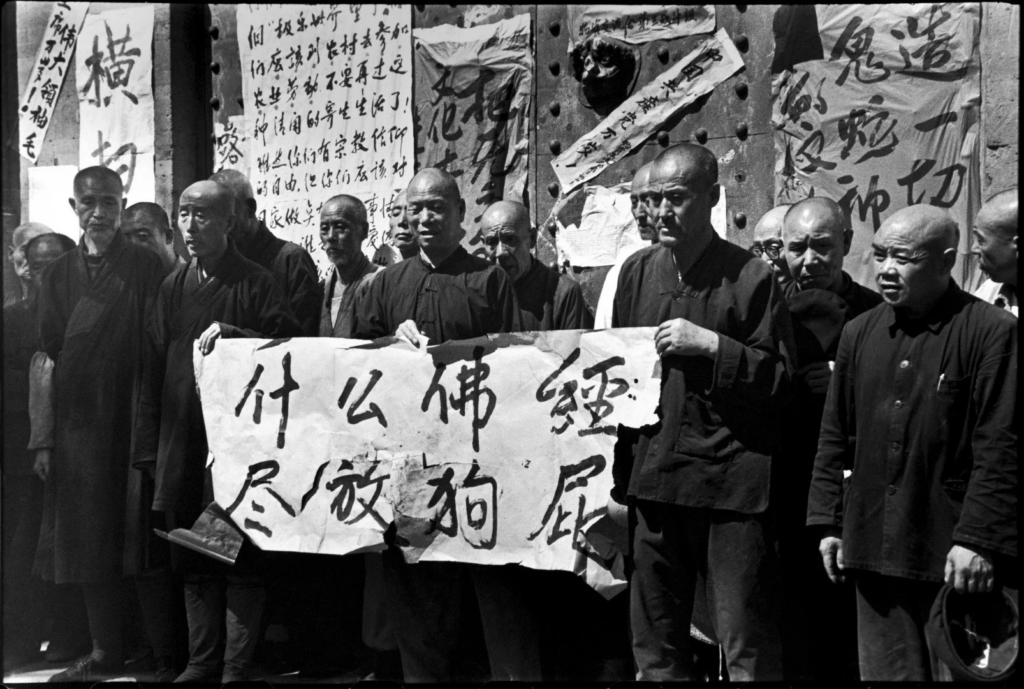

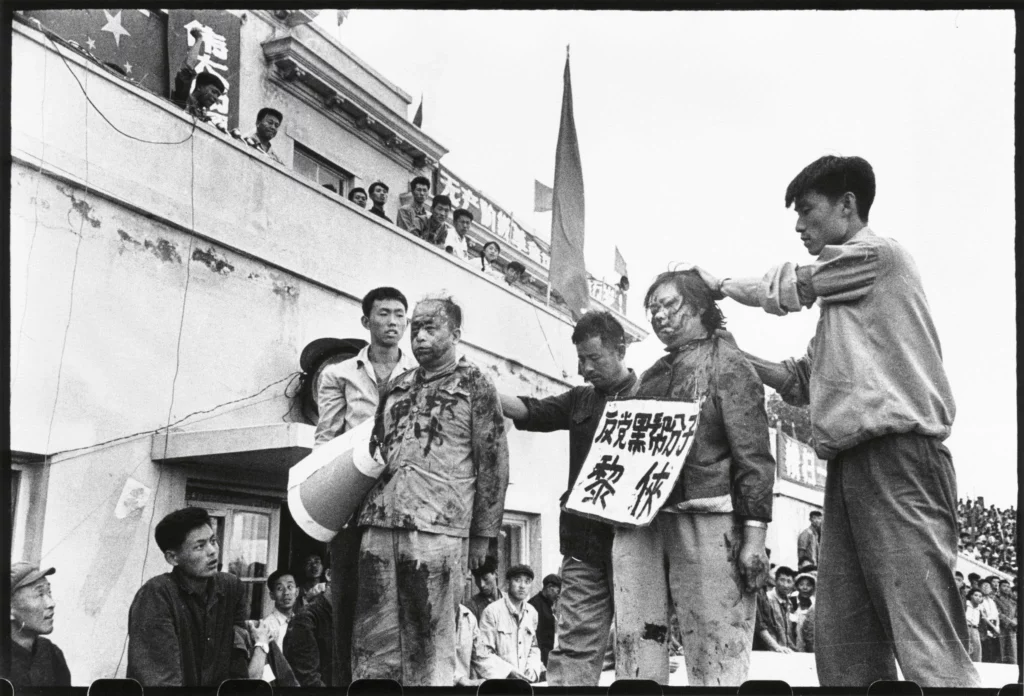

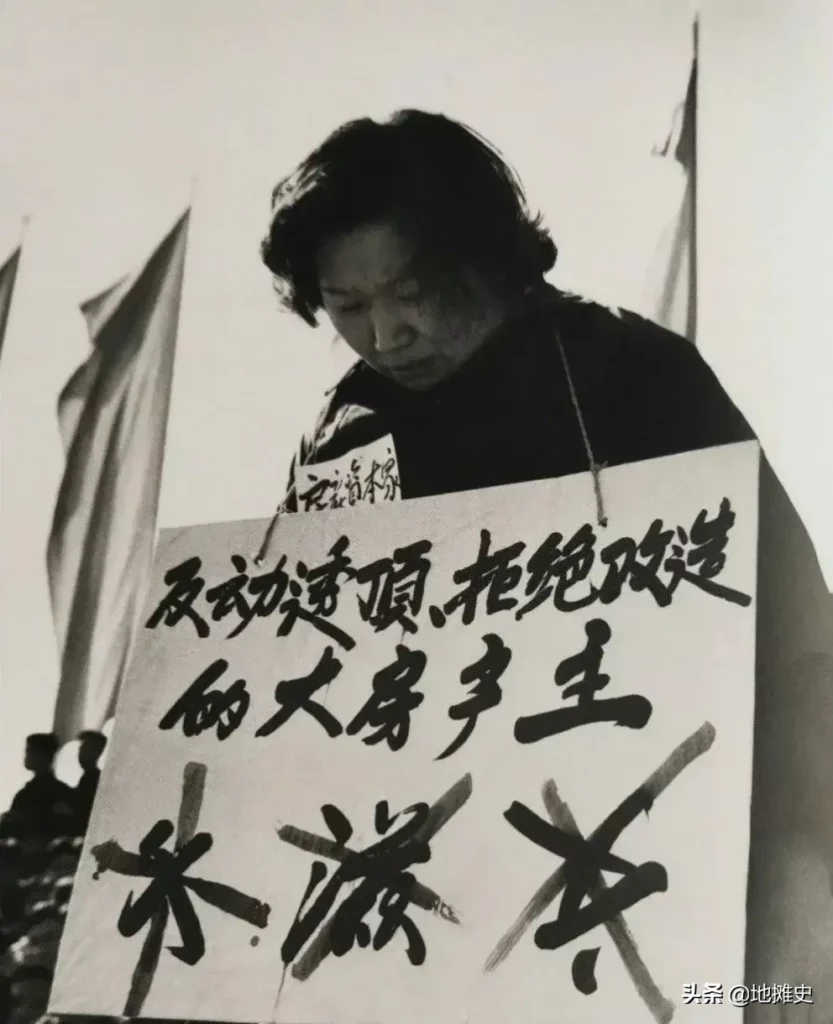

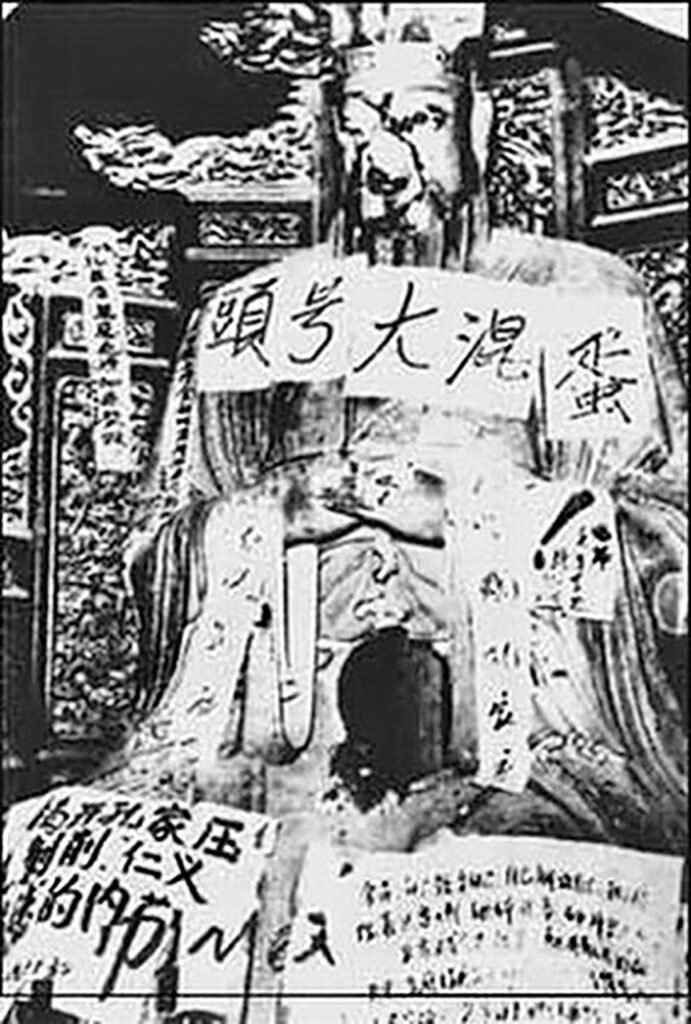

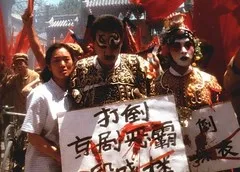

Those interested may want to take a look at the Cultural Revolution photographs taken by Li Zhensheng. He was a news photographer who took a multitude of photos during the Cultural Revolution – essentially an official photographer of that time. However, he privately saved many unpublished photos, which he kept until after the Cultural Revolution ended. These have become some of China’s most extensive records of various aspects of society during that period.

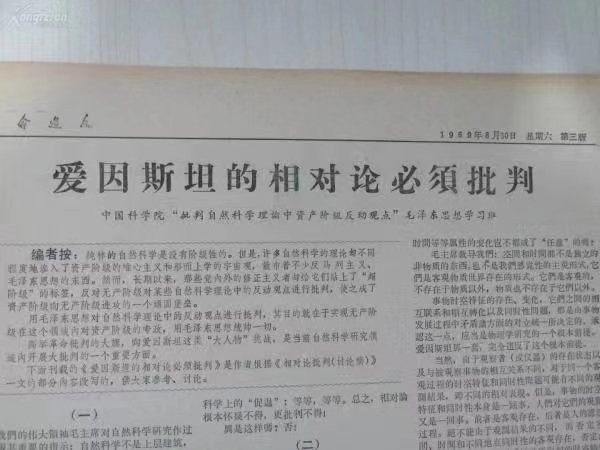

“The Three-Body Problem”‘s Cultural Revolution scenes

Li Zhensheng’s photo (Ren Zhongyi being criticized)

Li Zhensheng took various types of photos.

Monks being criticized (Jile Temple, Harbin)

Officials being criticized (Li Fanwu, Secretary of the Heilongjiang Provincial Committee, and his wife Li Xia)

Some ordinary people being criticized (the major property owner Yu Zhiwen)

Technicians from Harbin Electrical Instrument Factory (Wu Bingyuan, Wang Yongzeng)

Various scenes of smashing, looting, and the destruction of the “Four Olds”

China has had many TV dramas and movies that have depicted scenes from the Cultural Revolution. But after watching the segment in “The Three-Body Problem,” I felt it was quite special and worth watching.

The Cultural Revolution was a very complex movement and turmoil that lasted ten years. In the midst, even senior officials like Deng Xiaoping experienced the so-called “three ups and three downs” (with the first occurring before the Cultural Revolution).

I’ve always called the Cultural Revolution a meat grinder, while many people think of it as a boomerang. A boomerang implies that if you do evil deeds, there will be retribution. Just like when you throw a boomerang, it comes back to you, and it might hit your own head. This is similar to the theory of Karma, the cycle of cause and effect. For instance, Wu Han, who once criticized Hu Feng, was later criticized himself—this is the idea.

But in my view, the Cultural Revolution was more like a meat grinder, meaning that no one knew who would be criticized next. People like Deng Xiaoping, who had once been a very good comrade-in-arms with Mao Zedong, was criticized. At times during the Cultural Revolution, he held power; at other times, he was criticized again, then later held power and was criticized again.

During the Cultural Revolution, it was the same with Zhou Enlai. Sometimes he carried out Mao’s various orders, and at other times, Zhou was the target of criticism, although he was never completely brought down. But as everyone knows, the campaigns against Lin Biao, Confucius, and Duke Zhou were, in fact, targeting Zhou Enlai.

Basically, anyone could have been killed in this turmoil. Very few people got through the Cultural Revolution completely unscathed.

The Cultural Revolution is too complex, so any work can only show you a glimpse, and can only describe the Cultural Revolution fragmentarily through the experiences of a certain person or a group of people. No film or TV drama, even those specifically about the Cultural Revolution, can give you a complete picture of the multitude of life during that time or a panoramic view.

The Cultural Revolution was an extremely complicated process, and it is even hard to clearly explain all of its various details and processes. There’s a lecture by Professor Qin Hui titled “The Mystery of the Cultural Revolution: Four Narratives and Historical Truth” you can check out.

Some people negate the Cultural Revolution but affirm the system; others affirm both the system and the Cultural Revolution. Some negate the system but affirm the Cultural Revolution, while others negate both the system and the Cultural Revolution.

It also involves the understanding of the Cultural Revolution by people with different identities and experiences. In the Cultural Revolution, both officials who were toppled and those who were not, cultural figures and the common people, including ordinary people who were affected and some of the destitute who felt they benefited from the Cultural Revolution, were involved. So, it’s a very complex issue.

For instance, take the novel and film “To Live.”

Both the novel and the film depict a scene where a struggle session is held in Fugui’s village, during which Long Er is paraded through the streets and subsequently beaten to death.

Long Er was criticized because he was a landlord and then beaten to death. Fugui was so scared that he wet himself on the street, because he was formerly a landlord.

Long Er had gambled with Fugui, taking over Fugui’s property, and so Long Er became a landlord. But if Long Er hadn’t taken Fugui’s property, Long Er might not have become a landlord.

Fugui felt that now he had become poor because Long Er had taken everything he owned, but at the same time, this had taken away his potential misfortune as well—a feeling full of the fickleness of fate.

From this perspective, it seems that someone who went from rich to poor, like Fugui, would be a beneficiary during the Cultural Revolution. But that’s not necessarily the case. In another novel by Yu Hua called “Brothers,” related to the Cultural Revolution, the father of the brothers, Song Fanping, is a poor peasant. Their family was much like Fugui’s, formerly of the landlord class but had squandered their wealth before the Cultural Revolution and even before the liberation. So at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Song Fanping got the local leadership due to his status as a lower middle peasant.

However, after the story of Song Fanping’s father being a landlord was discovered, he was immediately overthrown and eventually beaten to death by the Red Guards.

Fugui and Song Fanping have similar backgrounds but ended up with entirely different fates.

I empathize with characters like Fugui and Song Fanping because my grandparents were very poor; our family was destitute after the liberation. But before that, my grandfather’s family was wealthy, once reputed to own shops on both streets of the town, but the previous generation squandered it all on opium. By my grandfather’s generation, the family was getting poorer and poorer. Initially, my grandfather had a better education and had served as an aide to a county magistrate. But later, when there was no more magistrate, my grandfather went from selling family assets to becoming a small merchant dealing with various second-hand goods. Eventually, our family lost all our houses in the county town and had to rely on living with relatives in my grandmother’s hometown, and originally, my grandmother was actually a child bride. You can see the speed of this downfall in fate is very much like Fugui’s story.

During the Cultural Revolution, it seems that our family was not much affected.

Among the old cadres of the Chinese Communist Party, some were overthrown, some were killed, and some were forced to jump off buildings. Chen Yi, He Long, Luo Ruiqing, Wu Han, and so on—each met a different fate because the reasons for their downfall and how it happened were also different.

There have been various films and TV shows that touch on different aspects of the Cultural Revolution, such as “Furong Town” and “Sorrowful Love.” However, many parts of the Cultural Revolution, such as large-scale armed conflicts involving tanks, artillery, and machine guns, seem not to have been depicted in any current films or TV series. For instance, the incidents of cannibalism do not seem to have been clearly portrayed either.

There might be descriptions in novels, reportage literature, and historical records, but these have not yet been made into films or TV dramas.

Where does “The Three-Body Problem” stand out? It’s unique in that the story involves the killing of a university professor whose crime was promoting Einstein’s theory of relativity and the theory of the Big Bang.

I once asked on Weibo—I posted a message asking if people knew that even Einstein was criticized during the Cultural Revolution. Many were surprised, wondering what Einstein had to do with the Cultural Revolution. Even though Einstein lived in the United States, how could the matter of capitalism and socialism be related to Einstein? Shouldn’t everyone be learning the same physics, chemistry, and mathematics?

We know that in China, the history, politics, and economics departments teach subjects that are very different from those taught overseas. Especially in economics, we have courses on socialist market economies as well as on Western economics, and the theories and viewpoints of these courses are completely different. However, in physics, chemistry, and mathematics, we are basically in line with the rest of the world.

But before the economic reforms, it was not like this. The Soviet Union had some academic disputes with the United States. For instance, there were differences in theories regarding genetics and physics, leading to debates. At that time, China took sides, siding with the Soviet Union. If the Soviet Union said Einstein’s science was pseudoscience, then we considered Einstein’s theories to be pseudoscience and capitalist physics. There were also such debates in mathematics, chemistry, and genetics.

The articles, papers, or big-character posters that criticized certain mathematical theories, the theory of relativity, gene theory, and the Big Bang still exist and can be found. But many people are not aware of this, so when I posted it on Weibo, it shocked many people.

Many people have seen “Farewell My Concubine” and “To Live,” and have seen some scenes of old cadres being criticized in films and TV dramas. However, they may not be able to imagine that, during the Cultural Revolution, discussing Einstein’s theories was also a crime. Even physical theorems could be criticized—relativity theory could be denounced.

The absurdity of the Cultural Revolution is not just a little nor fleeting; it’s boundless.

The Cultural Revolution is a very complex event that can’t simply be described as a single trend. Instead, it was a chaotic dance of various ideologies under certain directives. It wasn’t purely grassroots spontaneity. There were, of course, spontaneous elements among the masses, but what kind of spontaneous actions were allowed and what were not is an obvious question in China.

Nowadays on the internet, some people criticize Nongfu Spring. I said, you think that the fact that Zhong’s son studied in the USA and obtained American citizenship is unacceptable. Then why don’t you dare to criticize Coca-Cola or Pepsi, the quintessential products of American imperialism?

Some people say it’s not that no one criticizes Coca-Cola, but rather, surprisingly, vilifying Nongfu Spring became popular, while no one paid much attention to the criticisms of Coca-Cola. This level of awareness, though better than assuming Coca-Cola is never criticized, is still quite superficial.

The reality is quite simple; you have to look at who Coca-Cola is in joint ventures with in China. In the South, it’s Swire Group, and in the North, it’s COFCO. COFCO is one of China’s top state-owned enterprises, with its chairman holding a vice-ministerial level position. COFCO is one of the most important state enterprises in China, responsible for the import and export of grain, including meat and oil.

You’re free to insult Nongfu Spring, but criticizing Coca-Cola might affect the interests of a significant state enterprise. So, do you think your opinion will be allowed to spread?

Like during the pandemic, when there were some issues with Disney, and people wanted to cyber-bully Disney online. Disney did display some customer-unfriendly behavior and was targeted by many. Then some said Disney is going to have bad luck with the anti-American sentiment so high in Chinese society.

I said at the time, look at who Disney is partnered with in China, do some research, and you’ll see that Disney won’t have any problems.

I discussed the Cultural Revolution before, and someone commented that the Maoist left doesn’t want to return to the era of the Cultural Revolution, but to a fair society.

I’m not sure if this person was characterizing the Maoist left or is part of it. I suddenly felt very moved—when did China during the Cultural Revolution become a fair society? Or was Mao’s era a fair society? Isn’t there some misunderstanding about a fair society and fair distribution?

I think the core issue still comes from the lack of a tangible understanding of the Cultural Revolution, and why China’s society before the reforms was on the brink of collapse; its economy, culture, politics—everything was on the verge of falling apart.

Perhaps it’s because there are too few literary works available. Right after the end of the Cultural Revolution, the situation was favorable; it was politically correct to criticize the Cultural Revolution. There were scar literature, films, and TV shows. However, as scar literature began to delve into deeper problems or touch upon the interests of some old cadres who still held power after the Cultural Revolution, you couldn’t dig any further—the wounds could not be reopened. Gradually, the Cultural Revolution became a national scar that was better left alone, unmentioned openly or in secret.

We can endlessly defeat Japanese invaders in TV and films. But why is there so little genuine discussion about the Cultural Revolution? Because it’s a sensitive topic, after all, a period of the party’s errors.

But what is the consequence of not discussing it? The history is slowly forgotten, especially without a vivid understanding.

Especially when some books and novels can mention the Cultural Revolution, but TV dramas and films are much less.

Like in the novel “The Three-Body Problem,” the depiction of the Cultural Revolution is indeed sharper and more explicit, but what caused more controversy was the Netflix adaptation. Because even for “The Three-Body Problem,” which is already the best-selling Chinese science fiction novel, in 2019, its sales even surpassed “To Live.”

But overall, the reading public in China, those who read novels compared to those who watch TV and movies, is still a niche group.

“The Three-Body Problem” sold 7 million copies, which is insane. Similarly, Liu Cixin’s “The Wandering Earth” made over 10 billion yuan at the box office, with 70 million viewers, despite the novel not being Liu’s most popular work. The movie’s revenue was ten times that of the best-selling novel it was based on.

It’s things like movies and TV dramas that the general public consumes, something concrete. But appreciating novels requires a higher level of engagement, and only a minority do, with most people preferring TV dramas and movies.

This is why censorship in China is stricter for movies and TV dramas than for novels, for example, the film adaptation of “To Live” was banned, but the novel was never banned. The novel “To Live” is more detailed, with a more impactful narrative, but the movie has a stronger visual impact.

That’s also why in the past couple of years, people have sued Mo Yan. But many years ago, Zhang Yimou was heavily criticized for films like “Red Sorghum.” Because critics of Zhang Yimou don’t read novels, many don’t even know who Mo Yan is or that the story behind the film is sourced from Mo Yan’s novels. Although “Red Sorghum” became popular and Mo Yan gained fame, he remained a niche celebrity.

It’s not necessary to treat the exact replica of the original novel in film or TV adaptations as a core point. Except for the minority who both read the original novels and watch the adaptations, most of the time, these are two completely different groups of people. Many avid novel readers, like myself, aren’t that interested in the domestic or Netflix adaptations of “The Three-Body Problem” because the structure of “The Three-Body Problem” makes it difficult to perfectly adapt into a film or TV series.

So should “The Three-Body Problem” not be adapted into film or TV? I don’t think that’s the case. Because there are countless people who don’t read novels, and they judge the adaptation on its own merits. Even if many book readers feel that the content isn’t perfectly replicated, for non-reader viewers, this isn’t an issue.

These are two completely different audiences. A movie I particularly like is “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” an American road movie.

I especially enjoyed “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” After watching the movie, which was quite long and had a complex story with travels to multiple destinations such as Iceland and the Himalayas, with scenes of skateboarding, jumping into the ocean, and spotting snow leopards, as well as volcanic eruptions, I was eager to read the original book. But upon searching for it, I found out that the original was just a short story published in The New Yorker.

Apart from the main character being named Walter Mitty and his characteristic daydreams disrupting his reality, the plot, characters, and story were completely different from the movie.

In the same year that “The Wandering Earth” became a hit, another of Liu Cixin’s novels was adapted into a film called “Crazy Alien.”

“Crazy Alien” is based on Liu Cixin’s novella “The Rural Teacher,” and the adaptation was quite significant, with many changes to the overall story. However, this adaptation didn’t face much criticism. Maybe it’s because “Crazy Alien,” as a film, didn’t retain much of Liu Cixin’s flavor, and “The Rural Teacher” isn’t one of Liu’s most famous works. Many people, even fans of “The Three-Body Problem,” may have not read it or might not have cared too much about it.

I generally think it’s best for a movie to have an original novel behind it. Purely scriptwriter-and-director-created films often lack a strong structure, whereas novels, unable to provide immediate visual stimulation, require the writer to work harder on constructing the background and structure. Therefore, novels are usually more grand, with better-developed story backgrounds and worlds.

But ensuring a perfect replication of a novel’s content in adaptations is difficult because these are entirely different mediums. Some things are presented well in films, others are better described in books. Some things may seem clever and enjoyable in a novel but lose their charm when translated to film. Conversely, some things are fascinating on screen but less so when written down.

I once read an article discussing the adaptation of the drama “Fortress Besieged.” It gave an example of how the novel described a meal where everything on the table was cold except the ice cream, which was steaming—something quite meaningful and interesting in the novel, but hard to convey in a film unless you use a voiceover, which isn’t the language of cinema.

For my part, I’ve been working with a subtitle software called TinyStudio. I’ve been exporting subtitles from my videos so that every episode on YouTube now comes with subtitles. After exporting, TinyStuido calls OpenAI’s ChatGPT convert the subtitles into an article.

The rearranged article requires checking for recognition errors, eliminating fillers, and correcting stutters. But that’s not the end of it; I also make modifications, deleting some content, adding new material, and changing certain parts. Why?

Because some segments in the video, when I was speaking, felt clever and interesting, but in article form, they don’t have the same charm. Some parts that seemed clear when spoken required additional details in writing.

Since video and writing are different mediums, the same content requires different ways of expression when delivered.

So, I think, if you want to watch a good sci-fi TV show on television, Netflix’s adaptation of “The Three-Body Problem” is definitely worth watching. If you’re a fan of the novels and want a perfect adaptation, you’ll likely be disappointed. But your disappointment doesn’t affect whether the TV show is successful. The director, screenwriter, and producers aim to satisfy their target audience and maximize commercial success.

Firstly, the target audience is not Chinese; when compared to Netflix’s primary audience, both readers of the Chinese and English versions of the novel are a niche group. The production team should focus on how to tell a good story on television, not on how to perfectly replicate a novel. TV shows have their own pacing and structural considerations, and they can’t be the same as novels.

Regarding whether the Cultural Revolution might return, I still have concerns.

However, Professor Qin Hui has given me much inspiration. I’ve forgotten his exact words, but the gist was that the future isn’t preordained. This is the significance of our existence and the confidence we should maintain.

We should always hope that the Cultural Revolution doesn’t return. We are all individuals without much impact on society as a whole. But at least if the scenario of Chairman Mao initiating the Cultural Revolution were to reoccur, we shouldn’t become the young activists who eagerly join the frenzy (though if I joined, I’d be among the elders). At least we shouldn’t be those people.

I once said a long time ago, and many people know this, society is often described as one that harms one another. You produce gutter oil but don’t consume it yourself; I make sausage out of bone paste and starch, and I also don’t eat what I produce. But you might end up eating the sausage, and I might consume your gutter oil. Such mutual harm in society is almost unavoidable.

How do we resolve a society of mutual harm? As individuals, we can’t resolve the societal damage. No one can stop when the grinder starts, and no single individual has the capacity to address this blood problem.

But I, at least, don’t want to become an accelerator in the meat grinder, nor a perpetrator contributing to a harmful society.

So, I believe the only way to address a society of mutual harm is to hope it becomes a society of unilateral harm. You may harm me, but I won’t harm you. At least for us, it’s not a society of mutual harm. At least I haven’t engaged in mutual harm. So, if the Cultural Revolution were indeed to reoccur, I, at least, would not engage in criticizing you. If you’re inclined to criticize us, I can’t do anything. I think this is the only common baseline we can adhere to.